✨ Smattering 04: Weird Times

Eclectic collections of fragments, quotes, and anecdotes from our on/offline lives.

“Modernist and experimental work often strikes us as weird when we first encounter it.

The sense of wrongness associated with the weird — the conviction that this does not belong — is often a sign that we are in the presence of the new. The weird here is a signal that the concepts and frameworks which we have previously employed are now obsolete.

If the encounter with the strange here is not straightforwardly pleasurable (the pleasurable would always refer to previous forms of satisfaction), it is not simply unpleasant either: there is an enjoyment in seeing the familiar and the conventional becoming outmoded — an enjoyment which, in its mixture of pleasure, and pain, has something in common with what Lacan called jouissance.”

From Mark Fisher’s The Weird and the Eerie (2016)

🌼Jouissance

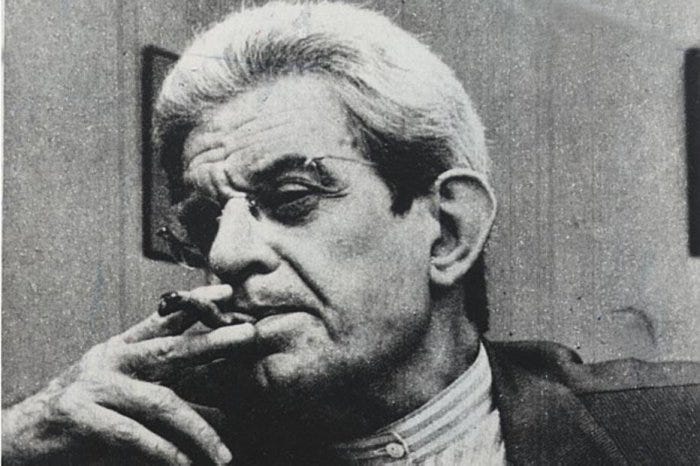

We are at the Catholic University of Louvain in the early 1970s. The lecture French psychoanalyst Lacan ("the most controversial psycho-analyst since Freud") is about to give is the only known recorded instance of his appearance in front of a public audience. He enters to applause, jokes with the crowd, and his performance thereafter is extremely theatrical.

When things quieten down Lacan recounts the story of a patient who, “a long time ago had a dream that the source of existence would spring from her forever more. An infinity of lives descending from her in an endless line.”

After a pause, the question he shouts at his audience, emphatically, is:

“Est-ce que vous pourriez supporter la vie que vous avez?”, which translates to,

“Can you bear the life that you have?”

🌖A Weirdened Excess of Life

Lockdown has laid bare the strangeness of the everyday. It has severed us from many of our routines, and coated those that survive with a deep glaze of oddness.

A permanent message in the corner of the television screen orders us to “stay at home”. Every journey beyond the front door must be justified. A queue for the supermarket is elongated by two-metre gaps policed by upturned baskets or stripy tape.

Once inside, we find that the shelves have been denuded of once banal and now treasured items such as dried pasta and toilet roll, and cashiers are shielded from us by Perspex screens. Freud would have called this the unheimlich: the troubling intrusion of the unfamiliar into the familiar.

In an English thesaurus, the word everyday is found alongside other words – dull, humdrum, workaday – which seem to dismiss it as unworthy of interest.

Would you call it boring?

In an essay on boredom from 1924, German cultural critic Siegfried Kracauer calls the everyday “a life that belongs to no one and exhausts everyone.”

😳The (so-called) Boredom of Everyday Life

France has produced an especially rich body of writing on the invisible vie quotidienne – a phrase both more precise and more evocative than the English everyday life. At the heart of this tradition lies Henri Lefebvre’s three-volume Critique of Everyday Life.

Published between 1947 and 1981, Critique covers the ‘Trente Glorieuses’, the thirty-year postwar boom that transformed France from an agrarian into a modern consumer society. Lefebvre explores how a new culture of consumption promised to relieve the drudgery of daily life, tapping into the desires – for style, glamour, energy, abundance – that this drudgery failed to fulfil.

Consumer culture pledges to replace everyday life with lifestyle and public tedium with private pleasures. In the final volume of Critique, Lefebvre foresaw that we would one day be able to shop without ever leaving our homes.

We will never break through the everyday to reach some more exalted plane of existence, for “man must be everyday, or he will not be at all” (Lefebvre). We dismiss the everyday as marginal and boring when in truth it is unavoidable and freighted with meaning. It recedes from view even as it fills up our lives. – Joe Moran

🛠Total Work

Total Work is a concept that comes from the book Leisure: The Basis of Culture by Josef Pieper.

Pieper defines Total Work as the state where work is the primary focus of life, but I don’t think that’s quite right. Work is not the focus of life, because you can be engaged in Total Work without being in work. e.g. the weekend as a break from work is still a part of Total Work. Even being unemployed is still, potentially, Total Work, because you are defining yourself with relation to work.

Under Total Work, work is not so much a focus as an orientation - everything in life is defined by its relation to work.

In the same way that sanity is not the opposite of insanity, unproductivity is not the opposite of productivity, because both orient the world around work.

❌Deleted Tweet

🌐'Instagram makes you feel part of the art world

—but it's a lie'

With galleries and museums shut for much of the pandemic, many people turned to Instagram as their main source of artwork. However, artist Rachel de Joode is sceptical about the app’s ability to introduce people to new and challenging work. “The algorithm is powered by machine learning… the more the Instagram algorithm thinks that I might like a post, the higher it will appear in my feed,” she says. “[It] is curating my ways of seeing art and it will put me in a comfortable, artificial bubble… you’re in an in a sort of algorithm loop that's just your own world.”

De Joode describes the central focus of her practice as the space between the physical and the virtual worlds. What she finds most interesting about Instagram is its ability to simplify and pacify. She says the app gives people a “false sense of validation”—a belief that the art they are viewing or posting is more popular than it really is. “You’re in a real simulation, you’re watching the party, you feel part of the art world, and you feel that you know what’s happening,” she says. “That’s a good feeling, but it is of course a lie… a rather soothing lie”.